Behind the Screen

November 24, 2020

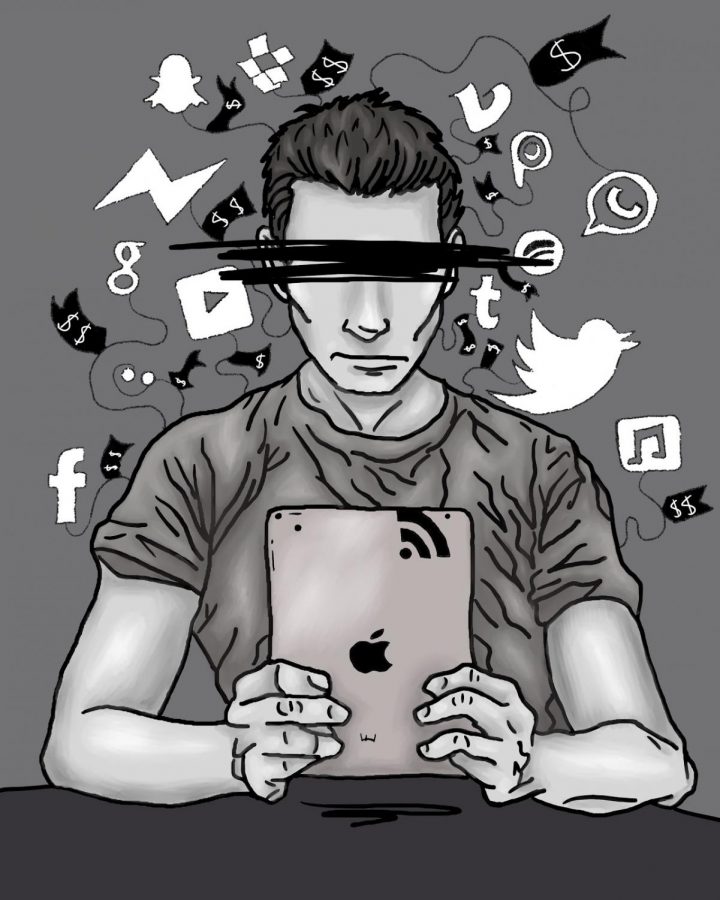

As the morning of Zoom calls comes to an end and you’re finally dismissed from your last class, do you find yourself reaching for your phone to open Instagram, Snapchat, or YouTube? Many of us do this instinctively, without thinking about what happens behind the screen every time we like, retweet, or scroll.

Just prior to writing this article, I watched the Netflix documentary “The Social Dilemma,” which touches on the overarching privacy and ethical concerns with social media. After watching it, I decided to delete the vast majority of my social media accounts: Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, even Pinterest. Privacy is extremely important to me, and the documentary made it clear to me that these online sites weren’t doing enough to protect its users’ data. Also, one glance at my feed made it obvious that the content being shown to me was essentially the same posts over and over again, with little differentiating them. With a few taps on my phone, the apps were gone and the accounts deleted.

While one proved necessary (Snapchat, to communicate with team members I hadn’t exchanged phone numbers with), all of the others didn’t and remain deleted. What I realized corresponded with much of the research I found while writing: my feed on these platforms was finely curated, composed of sponsored and recommended posts that didn’t require any critical thinking—since their only purpose was to sell me something or to vocalize opinions I myself already had.

After distancing myself from social media, I didn’t find myself lacking essential updates or news. If anything, I had more time to read up on more unbiased, and trustworthy news that was not affected by my likes or activity on social media.

A common saying in the tech industry, quoted in “The Social Dilemma,” is: “If you aren’t paying for the product, then you are the product.” On social media sites, which are often free of charge to use, are we actually the product?

In search of the answer to this question, it’s important to consider the advertising that keeps these sites running.

According to Jasmine Roberts, author of “Writing for Strategic Communication Industries,” “Advertising is the paid promotion that uses strategy and messaging about the benefits of a product or service to influence a target audience’s attitudes and/or behaviors.”

But how do advertisers know which online accounts are most likely to be receptive to what they are selling? This inquiry normally follows with the default answer: “Social media sites can sell our data to advertisers.” However, that’s not exactly the case.

Can Instagram or Twitter compile all of our information into a folder and ship it to an advertiser? Not exactly, but that’s pretty close to the reality.

According to Kalev Leetaru, a senior fellow at the George Washington University Center for Cyber & Homeland Security, although social media sites can’t directly give out your information, they still can use your information to give you targeted ads that, if clicked on, can give away some of your information.

First, social media sites ask advertisers who their target audience is, whether that’s adults who enjoy baseball or high school juniors preparing for the ACT. From there, social media sites can deliver their advertisements specifically to the accounts that match the demographics they selected. If a user clicks on that advertisement, the advertiser can track their IP address and can trace it back to the user, revealing their identity.

The information that these social media giants use to connect your account to the “right” advertisers is gained by tracking your actions on their site. Each action that you consciously make on the site—including every comment, like, and saved photo—is a puzzle piece used to create a more complete identity of who you are according to the site.

This identity is mainly used for prediction purposes; your virtual identity allows them to guess what posts you are most likely to engage with, what advertisements you are most likely to be interested in, and what posts will keep you on the app for as long as possible. Tracking doesn’t even stop at the actions you do consciously.

According to Facebook at about.fb.com, in 2015 their site updated the “News Feed’s ranking to factor in a new signal—how much time you spend viewing a story in your News Feed.” Every time you linger on a Facebook post, that activity is being tracked and influences what shows up on your News Feed.

One of the main concerns with this type of advertising is that it locks users into an echo chamber, where the only posts they see on their feed are those that reaffirm their own beliefs.

C. Thi Nguyen, associate professor of the University of Utah, says, “An echo chamber leads its members to distrust everybody on the outside of that chamber. And that means that an insider’s trust for other insiders can grow unchecked.”

If we begin to trust the information of others in our echo chamber without fact-checking, we can become more susceptible to fake or misleading news.

In this way, these sites act as a manipulator through radicalizing our beliefs while neglecting to show us the diverse perspectives and ideas of others.

Considering the lack of privacy and potential for manipulation, is it time to throw in the towel on social media? Maybe not.

Emma Lovell, a senior at SHS who runs the social media accounts for both DECA and Key Club at Stoughton, comments on the benefits of social media. “For me personally, it’s a way to connect with my friends and see what they’re doing, and it’s also a way to express yourself and have a unique style on your posts or feed. [It’s] a way to interact with others outside of your friendships at school and you can meet people from around the world.”

She continues, “I think [having a social media account] is a really big part of the club[s]…just showing off what we have in [the clubs] and what we’re doing, and also reminding of upcoming events…[It’s] not necessary to have it, but it’s a good way to connect with others and engage in the club[s].”

Personally, I found that most of my social media accounts weren’t essential and weren’t worth the risks they came with, although some warranted a place on my phone for the unique connections they could provide. Social media comes with the advantages of instant updates and virtual connections, but at the cost of privacy and potentially misleading information thrown our way. Is our reliance on social media justified, or can we make use of alternatives that place a greater emphasis on our privacy than our profitability?