Feeding America

Farmers: the backbone of our society

April 30, 2021

That half-eaten apple rotting in the trash, those vegetables that lay on the side of a dinner plate–how did they get into our hands? Aside from the obvious grocery store visit, what went into producing our food and delivering it in the (usually) pristine condition we all purchase these goods in?

The farmers that feed America, that work tirelessly each day regardless of weather, are the backbones of our world. They are the reason we have access to spices and fruits, to fresh vegetables, milk, beef and cheese.

While their office may be a field and their car a big tractor, the life of a farmer isn’t for everyone. Depending on the farm, some farmers wake up at the crack of dawn to milk cows and feed calves, to tend to newborn babies or ailing animals. Other farms are more laid-back, if you can even say that, and are only open with the seasons.

It’s not always easy to find a farmer who isn’t swamped with work. Luckily, in a small town like Stough

ton, we’re surrounded by a large variety of farms and farmers, most of whom are eager to share their stories, experiences, and lifestyle with anyone who will listen.

High school senior, Makayla Ramberg, works on her family’s dairy farm when she isn’t taking care of horses at Three Gaits, a horse stable just west of town.

Her grandparents started the farm many years ago and had over 60 cows, but there are now only about 20 female cows and the farm is operated solely by her grandparents.

Ramberg likes to head over to the farm to help out as often as she can.

“I feed the cows the grain that they eat while they’re milking. I help put hay out in the pastures, and I do a lot of work with the calves and put them into their new pens once they get older… Besides that, I work a lot with whatever-aged animal that I’m going to show at the fairs,” Ramberg says.

In the summers, Ramberg spends a lot of her time training calves to be shown at fairs. However, she also helps milk the cows whenever she gets the chance.

The milking process is tedious, as the farmers want to ensure that the teets don’t get infected, but it’s crucial that cows get milked… and, of course, they love it.

“First we clean up the utters – we especially make sure the teets are clean so when we hook up the milkers on them, there isn’t dirt that can get into it […] When we’re done milking, we unhook the utters and the milk goes into a bucket. The milkman comes every other day and unloads the tank and hauls it to wherever they take it to, and there they pasteurize it, clean it, and put it into milk jugs, and that gets shipped to the store,” Ramberg says.

The milking process is also key in allowing farmers to tell the health of their cows.

“If a cow doesn’t give all its milk, there’s something wrong with it,” Ramberg begins. “You can look for [the] signs, and if it gets bad, you should call the vet. [Cows] have a cool cycle where they dry up and stuff depending on their gestation period, too.”

When working on a farm, there are many special things that farmers get to witness on a daily basis. Ramberg’s favorite parts are witnessing the birth of a calf or even assisting in some births when it’s needed.

“If [the calf] has trouble, we’ve had to pull a calf from the cow – that’s definitely the coolest thing. The mom knows what to do by cleaning it and licking it off and helping it stand up […] We don’t let the babies stay with the moms too long because it ruins the cow’s udder–the calf will suck too much on one side and the udder will sag in one spot and not the other,” Ramberg notes.

A lot of farmers refer to a new mother’s milk as “liquid gold,” for it’s incredibly rich in nutrients and antibodies. This colostrum, as it’s officially called, is crucial for newborn calves to drink. Without it, the calf’s chance of survival decreases drastically. Dairy farmers often don’t like to leave the newborns with their mothers for too long, not only because it can cause damage to the udders, but the baby then consumes all of the colostrum, preventing it from being produced in the milk.

Once the calves start to grow, they soon become a perfect age for showing. Choosing the perfect calf, however, is much more challenging than it seems. Ramberg and her grandfather walk through the barn in the early spring, hoping to find an award-winning calf.

“You really want them to have a good udder because that’s what they’re judged on the most. You don’t want it to be too low or attached too high–you want the teets to lay nicely. You look for the strength in the cow, it’s called dairy strength,” Ramberg says.

Two years ago, Ramberg won grand champion at the Stoughton Junior Fair for her Ayrshire cow, and received a huge purple ribbon.

Ramberg plans on attending UW-Platteville to double major in agribusiness and dairy science.

Her time on her family’s dairy farm has helped her develop a love for working with large animals. Six months ago, she realized that she wanted to pursue a career as a calf and heifer specialist.

“That means that I’ll travel to farms to work with farmers to let farmers know how their calves are doing and [provide] them nutrition tips, [like what to feed them],” Ramberg says.

While dairy farmers certainly have high-intensive jobs that require constant attention, so do other kinds of farmers as well.

Eugster’s is a well-known farm for anyone living in the Stoughton area. Not only is it a highly regarded place for high school students to work, but it also hosts many events year-round and provides enough food to feed a village.

Juggling a full-time job at a family farm and earning her degrees in agriculture and business at the University of Wisconsin-Madison may be a difficult task, but SHS alumna, Katherine Eugster, has happily taken on that challenge.

On days where Eugster isn’t in class, she and her family wake up between 6:45 a.m. and 7:00 a.m.

The other workers typically arrive at around 8:00 a.m. during the spring and 6:00 a.m. during the summer.

“You want to harvest before it gets hot, otherwise the produce dries out and so do [the] flowers. If you harvest it in the hot sun, then [the produce] goes bad faster because it doesn’t have any moisture […] in it,” Eugster says. “You want to harvest either very early in the morning or in the evening.”

The 350-acre farm is home to dozens of different fruits and vegetables, along with an assortment of other goods, as well.

“We have the market garden which then produces broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, zucchinis, eggplants, cherry tomatoes[…]. We have two big greenhouses and we’re just putting up the third big one […] In the big field, my dad grows sweet corn, beans, cucumbers, [and] melons,” Eugster says.

Despite such endless space for fields, a large sum of the Eugster’s property is covered in trees and the Badfish River, preventing the Eugsters from opening up a lot of the land to the public.

Nevertheless, Eugster enjoys spending time by the water or in the woods with friends.

Eugster’s farm market primarily sells goods that their crops have produced, but every now and then they’ll sell products from other farmers, as well.

In the past, Eugster’s farm had bought honey from local beekeepers to sell in their market, but this year they will be debuting their very own honey. There are currently 17 beehives on the property, all of which are tended to by Eugster and her older brother.

“You have to get used to [the suit] because there will be bees buzzing four inches from your face–you have to trust that the suit is going to protect you. They’re their own animal. You look for the babies, make sure the hive is thriving, and make sure the queen is doing her job. It’s not too much maintenance […] It’s so exciting to see fresh honey that came from the flowers on your farm,” Eugster says.

Along with beekeeping, there’s never a dull moment on the property. Eugster loves the spring when the farm hosts ‘lambing and kidding days’, where people are able to come and hold newborn baby animals – from goats to kittens to puppies and more.

In the early to late summer, the farm is filled with sunflowers and the farm store, which sells various goods grown on the farm and a few imported goods like ice cream and popcorn, as well. In the fall, the farm hosts Screamin’ Acres along with the Fall Festival and other fall traditions such as apple picking, tractor rides, and apple cider donuts.

Even in the winter, when most farms aren’t able to sustain their planting and crop growing, the Eugsters still keep at it. In addition to tending to their animals and raising plants in the greenhouses, the Eugsters also sell Christmas trees in December.

Christmas trees have been a recent addition to the Eugster farm, sold for the first time last Christmas. The process for growing these trees and finally being able to sell them is a never-ending road.

“It takes about 10 years for the trees to mature, so we started planting the Christmas trees when I was 8 years old and we started selling them when I was 18,” Eugster says.

While she doesn’t do much of the maintenance for the trees, she does note that there is plenty of work required to shape them into the trees that a lot of us decorate in the winter.

Although Eugster’s is primarily led by the family of four, they wouldn’t be able to do it without the many helping hands on the farm.

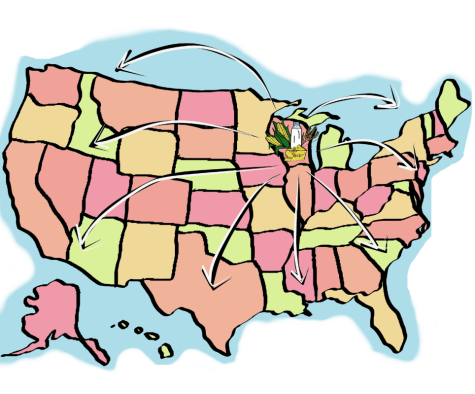

Aside from 15-60 teenagers and young adults depending on the season, the Eugsters house workers from Mexico, as well.

“In the spring, summer, and fall, we have five H-2A workers, which are people that legally come from Mexico, and they work on our farm full-time. They do a lot of the vegetable picking and we would not be able to function without them–they’re like a part of the family,” Eugster says.

She also notes that oftentimes, farms pay for housing and transportation for the H2A workers, but the Eugster’s have built a small house on a loft that they had on the farm, enabling the workers to work full-time on the farm for the many months that they stay there.

Living on a farm with people constantly around, peace and quiet is hard to come by. Eugster notes that she didn’t always love having others on their property, but says that she’s grown to love it and adores introducing people to farming and an agricultural lifestyle.

“When I was younger I used to say, ‘I want our farm back and I can’t wait for November’. But honestly, having people come out and learn about agriculture, learn about the importance of farming and eating local, and meeting farm animals for younger kids that don’t get the chance to be introduced to farm animals [is really special],” Eugster says.

Being a farmer is undoubtedly hard work and fairly unpredictable, especially as a student. Farmers face constant weather changes, different seasons for planting or harvesting, events that require countless hours of work–the list is endless. Nevertheless, Eugster enjoys the variability in each work day, as well as the outdoor aspect of the farming lifestyle.

“Some days you’re planting, some days you’re milking goats, some days you’re taking care of animals and giving vaccines, some days you’re picking flowers, so it’s definitely a very varied job, and I like that. I like not having to have the same routine [or the] same projects every day,” Eugster says.

In the future, Eugster and her older brother plan to take over the family farm… but they don’t see that happening for quite a while. Eugster’s parents, too, love working on the farm, and plan to do it for as long as they possibly can.

Blue Moon Community Farm is an organic CSA located just outside of Stoughton. This CSA (community-sponsored agriculture) is well-loved by Stoughtonites and other families, as well, with about 200 members each year.

Unlike Eugster and Ramberg, Kristen Kordet (owner of Blue Moon Community Farm) wasn’t born into farming. Instead, she came into farming as a consumer. For a while, she was unsure what to do as a career, but came across farming from an environmental aspect and through curiosity, which sparked interest in wondering where her food came from.

Kordet hopes her farm brings people together and enables them to learn how to grow food sustainably while developing a connection. She explains that her CSA works like a subscription.

“People purchase a share at the start of the season and then they come to the farm each week to get a collection of vegetables, whatever is in season, throughout the year,” Kordet says.

Subscriptions to the CSA usually open in early February, because that’s when the majority of the expenses occur. Kordet enjoys this method and likes getting to develop a personal connection with those who purchase goods from her farm.

“They’re our customers but they’re also pledging their support […] They’re members of the community of the farm and that’s great. We get to know people […] A lot of our families have been with us for many years. It’s nice to know exactly who we’re growing food for,” Kordet says.

At Blue Moon, they grow about 30 different things depending on the season. In the early spring, some of their produce includes salad greens and lettuce, followed by tomatoes, carrots, and squash in the summer. When Wisconsin winters hit and the growing season is complete, the farm simply goes indoors, to their greenhouses, instead.

This CSA in particular is organic, an aspect that benefits both the consumers and the environment. Remaining organic, however, isn’t always an easy process.

Kordet notes that there are a lot of little things that she has to think about in order to maintain her status as an organic farm.

“On a vegetable farm, so much of it comes down to our sourcing. Where our seeds come from, where our fertilizer comes from, what types of products we can use on our crops and what kind of pest controls are safe enough for the environment that we can use safely in an organic system,” Kordet says.

Caution doesn’t just apply to her own farm, either. Kordet has to think about her neighboring farms–do they use pesticides that could travel down the hill onto her property and contaminate her soil?

Is her property higher or lower than surrounding farms, and will rain or wind blow chemicals from nearby farms onto her land as well?

Thankfully, Kordet has it under control, and is able to maintain an organic status on her farm.

Despite being a farmer for around 20 years, Kordet didn’t major in environmental science alone. In 1999, Kordet graduated from Denison University in Gransville, Ohio, with a degree in environmental science as well as modern dance.

“They had a really great environmental science program, and also a small but really amazing modern dance program and I had been doing a bit of a dance in high school,” Kordet says. “I wasn’t great. I certainly wasn’t on a career path, but the department had money and so part of my college was paid for by having a dance major.”

On her farm, Kordet has around eight employees, a couple of which work part time with the remainder working full time. In addition to these employees, the farm also has a group of individuals that work in exchange for fruits and vegetables from the farm.

“We have a group of folks who are in our CSA program, but they barter for their vegetables,” Kordet says. “Some people work in the field, some help with the distribution of vegetables when the CSA members come, some people help us at the farmers market.”

Throughout the CSA season, Kordet and her farm host various events to bring the community together. Sometimes that entails opening up vegetable picking to the public, regardless of one’s membership to the CSA. Other times, there are little celebrations at the end of the season where all members come together for a movie and food.

As one looks down on their home-cooked meal, their microwave dinner, or even their Happy Meal, it may seem difficult to believe that almost everything on their plate came from a farm in one way or another. Whether it’s the glass of milk that we were all forced to drink from a young age or even the wheat that was used to make your cheeseburger bun, you have farmers to thank for all of it. Without them, our society would be fruitless… literally.