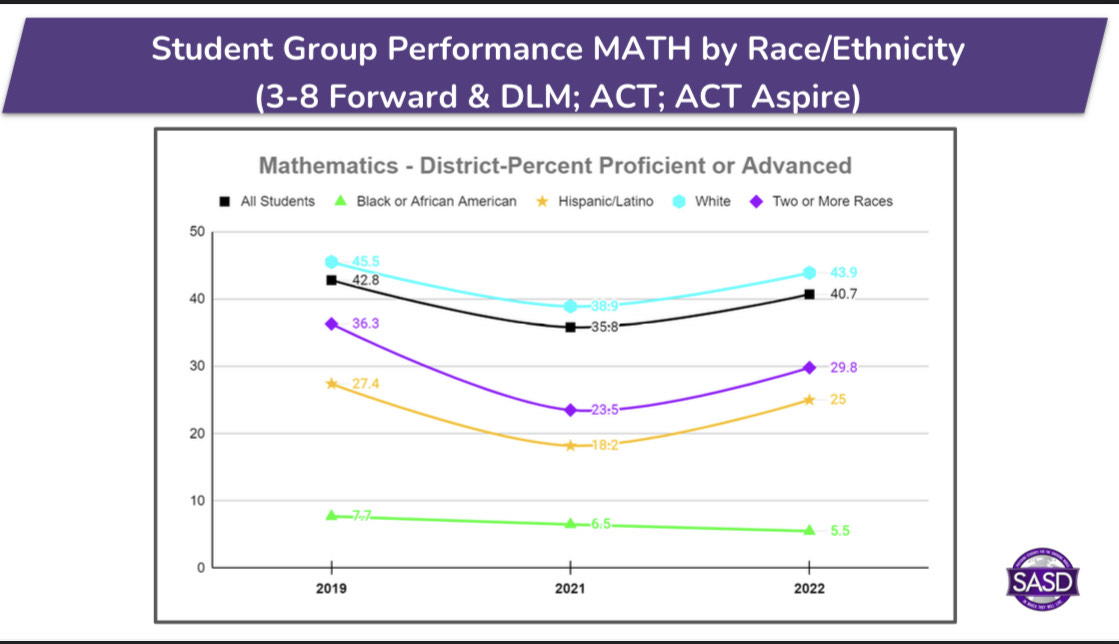

As a district that strives for progress, the Stoughton Area School District has launched a plan to close the gap between those who can and those who can’t reach the expected level of where they’re meant to be in a recent school board meeting. Another name for that gap is the “achievement” or “opportunity” gap—which lies between students who can digest math, literature, and the likes—and those who don’t fall into that category. It’s traditionally measured using standardized tests that are taken in school, which includes the ACT, SAT, STAR, and others, but can also be informed by in school participation and class grades.

Where did this push for a greater understanding come from? All of it stems from when state School and District Report Cards began to form. Before those, schools looked at their students and how they compared to the surrounding community. After those report cards came into play, it created a standard that spanned the whole state. This allowed schools to compare with others and determine how they were doing from there.

The gap isn’t a Stoughton-only issue. It spans the United States, though Wisconsin has one of the highest gaps in the country. As the principal of Sandhill Elementary School, Bob Johnson has experience on the topic.

“There are many different achievement gaps when you look at different groups.” Johnson said. “Traditionally, the students that have done well in schools have been white female students as the highest achievers. That comes with [many] different rationales for the history of how schools have been operated over the years. But you can see that there are gaps between that group or other groups. I believe that the achievement gap starts right at the beginning.”

Johnson believes that without a solid reading and writing foundation in elementary school, kids can fall behind. By the time they reach high school, getting them back on track for expectations of their age can be difficult. This can stem from multiple issues, plenty of them having to do with the fact that some students simply just don’t start learning at the same level as others. For example, it might be simple for a little girl to finish her homework as an only child. However, if that little girl has two smaller siblings that she needs to take care of because her parents are working double shifts, then it will be more difficult for her to keep the same pace as her classmates.

“We’ve lowered the rigor for many of our students who we maybe have [an] implicit bias about or don’t believe they can do it. And so by not giving them grade level curriculum, they actually are just not achieving, not because of what they are doing, but because of the expectations and the opportunities we’re giving them.” Johnson said.

The first step to narrowing that gap then comes down to removing the implicit biases and hurtles that students may be facing before they’ve finished kindergarten. This includes building support systems for the children in elementary school to receive tutoring in and out of school for things they may be struggling with, and breaking down how teachers perceive their students. And past the biases comes the actual model of the classroom.

As the Director of Student Services, Keli Melcher works daily with what students are dealing with in the classroom and out of it. Correspondingly, Melcher is also working to address the achievement gap.

“Belonging is a big help in closing some of those opportunity gaps because if a student feels like they belong in the classroom and they’re part of a community, it’s going to help them learn and grow. If they don’t feel they belong, they may not want to learn.” Melcher said.

A developmental learning day was provided for teachers of grades 6-12 that discussed this in August. The goal for this was to introduce the same things Melcher mentioned, which included strategies to invite more group discussions to the classroom.

Additionally, there have been changes made to the elementary curriculum. For grades K-2, the science of reading has been implemented in place of the workshop model. The workshop model leaned into “guessing games” rather than fundamentally understanding. If, for example, if a reader came across a word they didn’t know, the method focused on what the word looked like. Approaches were supposed to focus on what was visualized when reading the word, or what the word rhymed with. Recent research showed this approach was not helping students learn the best they could.

Act 20 introduced the science of reading to elementary schools in 2019. The method focuses on decoding and breaking down words so that when readers come across unknown words they sound them out. Alongside the science of reading, a knowledge-based program is also put into play. Readers are first taught letters, how they interact, and how they sound within a word. Using this method, readers are taught how letters form words. After that sticks, vocabulary is taught next.

“As soon as you start to understand what those words mean, you can then understand what those words together mean, which leads into comprehension.” Johnson said.

Along with these new methods being put into play, adjustments are also being made to the middle and high schools. At the middle school, staff have been working to put in an integrated studies block, which is meant to act as a “what you need” time for students. They can move between teachers based on their needs. At the high school, other adjustments have been made. Practices are more generalized, like implementing tutoring and online systems for anybody struggling. The school system can then look at these systems and decide what’s working and what isn’t.

“We’ve seen really great growth and progress in what we’ve been doing, and understand that we also have work to do to continue this. We want to support our students, our families, and our teachers and know that we’re all in this together.” Melcher said.

As the District Administrator and general overseer of all schools in the district, Dan Keyser shares his final thoughts on the topic as a key contributor.

“I think the achievement gap is always going to be something we struggle with. Do I think it’ll ever get to zero? No. I think we will always be finding ways to meet students’ needs,” Keyser said. “So I don’t think it’ll ever be zero, but if we don’t strive to try to close that gap, we’re not growing ourselves and our students. […] Stoughton has great schools, we will continue to have great schools, and we’re not going to lose sight of that. We want this year to be better than last year and we want next year to be better than this year. As long as we keep that holding that at our core, we will continually try to evolve and become better.”

Categories:

The Achievement Gap

0

More to Discover

About the Contributor

Naomi Matthiesen, Associate Editor-in-Chief & Website Manager

Naomi is a senior, and this is her third year on staff! She is this year’s associate and the website manager. She joined the Norse Star because it was a cool publication that she wanted to be a part of, and she loves writing. Besides the Norse Star, she’s in art club,book club and environmental club. Naomi enjoys math and stem-related activities, and she is interested in a variety of creative fields, such as reading, writing, drawing, and baking! After high school, she wants to enter a science-related field but preferably chemistry!