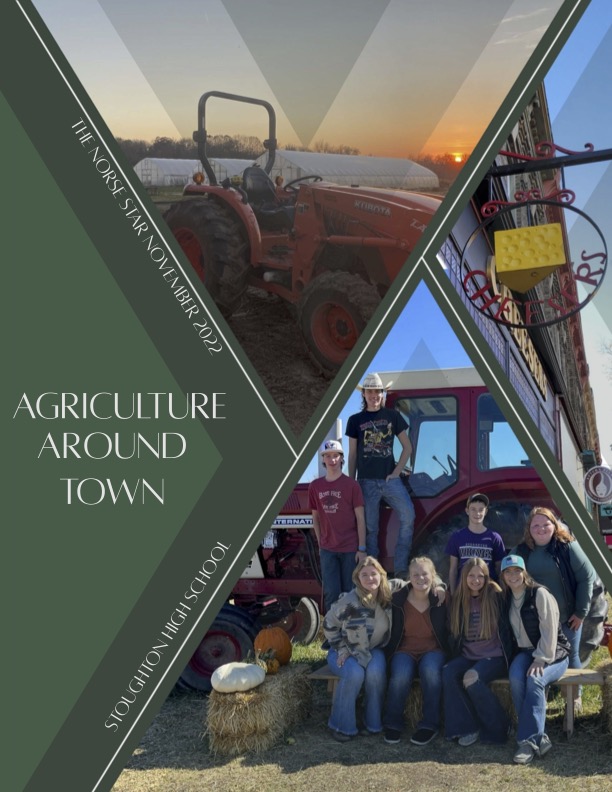

Agriculture Around Town

The Stoughton community has a rich history of farmers and agriculturalists. It makes sense, considering Stoughton is right in the heart of southern Wisconsin, a location primarily known for its fertile farmland. The farmers caring for this land are oftentimes continuing the legacy created by the generations of farmers in their families before them. Other times it’s an ambitious individual following their dreams, exploring their passions, or fulfilling a hobby. Regardless, their efforts to innovate new farming methods, grow fresh crops, craft delicious products to sell to the community, and create new and long-standing traditions are difficult to miss.

Nurturing the Future Generations of Agriculture

Stoughton has many opportunities for students to become involved in agriculture. The two most prominent agriculture clubs in the area are FFA and 4H.

Samantha White, the new agriculture teacher at SHS, also became the new FFA advisor.

The vice president of FFA, Hailee Kellnhofer, helps with any unfilled positions or unmade decisions. She also takes any steps to support the president, senior Claire Spilde.

“FFA is an extracurricular [activity] that you can join for fun. It stands for Future Farmers of America. You do not have to live on a farm to join. That is the most stereotypical thing that everyone says,” Kellnhofer says.

The opportunities available for student members are more than being involved in farming or animals. There are other opportunities for students who want to go into biotechnology or similar agriculture fields.

“You don’t have to be interested in going into agriculture after school. FFA is an organization for everyone who wants to become a better leader. [We] focus on some of those career-ready skills like resumes and job interviews. We have contests for that,” White says.

FFA even had a booth at freshman orientation for upcoming high school students to gain information about FFA. Officers and their adviser, White, are looking for more opportunities to educate the community on FFA and agriculture.

“The biggest challenge is kids not knowing what agriculture is all about. I wish more students knew you don’t have to be a farmer. If you like to eat, you’d like agriculture classes because we talk about food all the time,” White says.

The biggest hurdle for the organization is for students to broaden their horizons beyond farming.

“A couple of weeks ago, we went to the National FFA Convention in Indianapolis, and we got to see the American Degree awards, and someone from Wisconsin got it, so that was really cool,” Kellnhofer says. “It’s super fun. You can get involved with a lot and there’s a bunch of leadership opportunities and learning, like how to speak in public and that kind of stuff.”

There are many ways to find information about FFA if students are interested in learning more.

“We have a Facebook page that I post things on. It’s Stoughton Agricultural Education and FFA. I post stuff from classes and FFA meetings, but anyone can join at any time,” White says.

Students interested can go to room 162 and ask White for a membership form. FFA members could also grab one for students. Meetings are on the second Monday of every month at 7 p.m. in the same room.

Along with being an FFA advisor, White has also been an adviser for 4-H.

“I have family members that are in 4-H. I went through the 4-H program. I actually used to volunteer a lot with the Stoughton Fair, and in the summer, I worked for the Rock County Fair,” White says.

Natalie Nelson, a senior at SHS, has been a part of the Stoughton 4-H Trail Blazers for over ten years.

“I show horses. You have to be in 4-H to compete at Dane County Fair and go to state. There are a bunch of projects you can do. You can show animals. You could even show artwork or anything you want to display. They judge it, and there are placings for ribbons,” Nelson says.

4-H meetings are on the second Tuesday of each month at Covenant Lutheran Church.

“We have a Facebook page for Stoughton, [4-H] Trail Blazers. You can contact me or look at the Facebook page, and then we can give you more information,” Nelson says.

4-H also creates an opportunity for members to go to nursing homes, give a helping hand, and participate in fundraisers.

“It’s really good for college applications, [becoming a part of a] community, and you can meet a lot of new people. It’s just overall a good club to be in and help the community,” Nelson says.

To remain in 4-H, members have to give a demonstration about any topic annually.

“You can do anything. One year I showed people how to make slime. One year I brought my dog in. It’s just a way to learn more about different topics,” Nelson says.

Demonstrations presented by other members are how she learned more about farming, agriculture, and other subjects.

“It’s just a really nice community to be in,” Nelson says. “And it is a lot of fun.”

Agriculture with Ms. White

This year, Stoughton High School welcomed Samantha White, the new agriculture teacher. This is her first year teaching at SHS. Becoming the new agriculture teacher goes hand in hand with becoming the new FFA advisor.

“I’m from Stoughton. I graduated from here in 2016. I was in FFA and 4-H in high school,” White says.

She graduated from UW-Platteville with degrees in agricultural education and science. Before coming here, she taught in Stevens Point for two years, and now she teaches all of the agriculture classes at SHS.

When taking agriculture classes with White, students can have hands-on experiences with geckos, rabbits, guinea pigs, sheep, and more.

White has been interested in teaching agriculture since before graduating in 2016 and she wants to give students more opportunities for the chance to be involved in agriculture.

“My sophomore or junior year of high school, I thought [teaching agriculture] might be what I wanted to do, so I went to Platteville for that, and it was definitely the right decision. I never looked back,” White says.

She took many different types of classes to get her degrees. White took animal science, plant science, agriculture engineering technologies, and business classes.

“Whether you buy your own groceries now or when you’re older, you have to buy clothing, you have to find a car. I want [students] to make the right choices on what’s right for them. I want them to know how to do their own research. To get that kind of knowledge about agriculture,” White says. “I teach a lot of animal science classes. We talk about being a responsible pet owner, and what that looks like, or what farmers are doing with their livestock. What they’re doing to better our world, feed us, and provide for us.”

With her background in agriculture, she hopes to educate students about the connections agriculture has everywhere and navigating this world to make the best possible decisions needed for their future where misinformation can spread fast.

“I like that I get to spend so much time with students [taking field trips] and other fun that they don’t necessarily get to do,” White says. “It’s bigger than just the class name.”

CHEESEing at Cheesers

The farm-to-table process varies across the board, or better said, the charcuterie board. All the cheese, meat, dips, pickled products, spreads, and crackers anyone would need to craft their dream charcuterie board come from various farms, bakers, and experimenters. Yet everything can be found in one spot in Stoughton at Cheesers Lokal Market.

Co-Owner Brian Johnson ensures that all the charcuterie board and everyday must-haves are available to Stoughton residents. His efforts ensure these products are available directly from the farm to the community. Johnson doesn’t just source from any farms; he sources most of his products locally.

Cheesers originally opened across the street from its current location in 1995, was then moved to its current location in 2006, and has been co-owned by Johnson for the past three and a half years.

Johnson has made it a point to bring a variety of products to the store, such as a large selection of wine and meat, all sourced from local farms. Cheesers also hosts a large variety of locally made jams, choc- olates, and honey alongside other local favorites.

“We have Mandt Honey Works here in the store. We’ve always had Cabibbo’s Biscotti, Bavarian sausage, Vindicator meats, […] and Babcock Hall Ice Cream, of course,” Johnson says.

Cheese is where it all started. It’s in the name, after all.

“A majority of the cheese comes from places [that are] pretty local; Monroe, Broadhead, there’s a lot of cheeses made in the area,” Johnson says.

Sourcing directly from local farmers has allowed Johnson to form connections with farmers in and around the Stoughton community, as well as with farmers all over the county and state.

“I’m a customer of theirs, they’re a customer of ours; it’s very reciprocal. It really promotes community. If I have an issue or if I really need [a product], I’ll call the person, and if you know them personally, it’s a lot different than if you’re talking to somebody in Chicago and you’re another customer [to them],” Johnson says. “Developing those relationships—it’s like having another list of friends.”

Johnson not only wants to support local farmers, but he wants the community to understand that the product they are getting isn’t something you can buy at your local supermarket chain.

“I think we’ve all learned we want to know where our food comes from. We don’t want to be eating a lot of chemicals and additives,” Johnson says.

When you buy fresh products from community farmers, “you can taste the difference,” Johnson says.

Locally sourced pro- ducts create learning opportunities for community members buying those products. Thanks to Cheesers’ new tasting room located on the second story of the building, customers can learn about and meet the crafters of their favorite foods.

“People can really meet the producers and learn more about the products and things they’re offering and even develop more of an appreciation [for the products]. It enhances people’s lives,” Johnson says.

The fresh products sold at Cheesers create bonding opportunities between Cheesers’ staff and customers, both regulars and newbies.

“I call a lot of customers by name. They know me, and I know them. It’s really nice,” Johnson says. “Curd Day is always a big day. [We have] fresh cheese curds. When we get somebody that comes in and says they’ve never had a fresh cheese curd—to give them one, and they go, ‘Oh, that’s what they mean by squeak!’ [It makes them] smile.”

From Bær Gård to Buyers

The Stoughton Community Farmers Market breathes life into the small parking lot on the corner of Main Street and Forrest Street in the heart of downtown. Every Saturday from May through September, market goers grab their tote bags and wagons to peruse the stands, which pop with a variety of freshly grown, baked, crafted, and carved items for sale.

Frequent fliers of the farmers market are sure to have noticed a stand sporting a white and blue checkered tablecloth and a large sign that says “organic raspberries.” The friendly faces behind the table are Fern and Richard Hosfeld, proud owners of Bær Gård, a hobby farm located on Williams Drive near Lake Kegonsa State Park. Bær Gård translates to “Berry Farm” in Norwegian and is true to its name. They raise seven varieties of USDA-certified organic raspberries alongside a limited number of blueberries, all set out for sale at the Stoughton Farmers Market each season.

Fern Hosfeld takes pride in her raspberries, the growth of which is a retirement project.

“By growing the berries and participating in the market, [Richard and I] work toward several other retirement goals such as being challenged, enjoying the outdoors, staying active […] and enjoying conversations and friendships made at the marketplace,” Hosfeld says.

Getting the berries to the market is a lengthy process. Complying with the many requirements in order to be USDA-certified organic is one of Hosfeld’s greatest challenges.

According to the USDA, organic growing methods integrate “cultural, biological and mechanical practices that foster cycling of resources, promote ecological balance and conserve biodiversity. Synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation, and genetic engineering may not be used.”

The Hosfelds grow their berries under these strict guidelines alongside many others that allow them to produce a USDA-certified organic product, something they take pride in.

To learn what requirements must be satisfied to be USDA-certified organic, Hosfeld encourages reading up on the topic at www.ams.usda.gov.

Other challenges include the invasive Japanese beetles, who are attracted to the raspberry plants and eat them. Another yearly and highly unpredictable challenge is the weather.

“If we get too much rain, [the raspberries] will lose their flavor, and I will not bring them to the market,” Hosfeld says.

Hosfeld hand picks and taste tests each raspberry batch before they are packaged for the public. If they pass the test, they are off to the Farmers Market for the community to enjoy.

“Our primary goal with this hobby is to give back to this great community by providing a healthy product and contributing to Stoughton’s overall community spirit,” Hosfeld says. “We are grateful for the meaningful friendships that occur at the market.”

While at the market, Hosfeld’s berries resurface positive memories with community members.

“Food evokes emotion,” Hosfeld says. “For many adults, we find that our berries bring back tremendous memories of spending time with a grandparent in their backyard raspberry patch—or enjoying their grandma’s raspberry jam.”

Community connections like these open up opportunities for Hosfeld to connect with individuals and share her knowledge in organic berry growing. She hopes to support and educate the community by “sharing [her] organic practice and insights with others who are giving it a try,” Hosfeld says.

Hosfeld hopes she will impact the community by educating and encouraging everyone to try their hand at growing their own produce in their backyard.

“We hope to inspire younger generations to grow organic raspberries to achieve their health benefits and enjoy their flavor,” Hosfeld says. “[We want to] inspire folks to adopt organic farming and gardening practices.”

Hosfeld advocates for buying local and believes that this, alongside environmentally friendly growing practices, could assist with global warming.

“To feed the world, you need all different kinds of farmers. […] If you buy local, you don’t need [to transport] the berries. That’s a really big deal, especially for berries because organic ones [come] from so far away,” Hosfeld says.

Hosfeld’s ability to sell her products at the Stoughton Farmers Market allows her to get immediate feedback from customers.

“This [feedback] gives us a feeling of reward, gratitude, and happiness,” Hosfeld says.

While deciding that growing and selling berries was what they wanted to do in their retirement, Hosfeld discovered that it all came back to the community.

“The community [has] wonderful people, activities, organizations, business people, and those are blessings for all of us in this community. We wanted to do something to add and give back,” Hosfeld says.

Timeless Traditions

Farming has remained the backbone of our American society for centuries. Farmers work from the chilly mornings in November to the scorching afternoon heat in July to provide us with the freshest food on our table.

Furseth Farms, Inc. is one of the major farms in Stoughton and has been around since the 1900s. While they grow crops such as corn, soybeans, alfalfa, and wheat, they also raise cattle. Senior Garrison Furseth is a fifth-generation farmer who plans on continuing his farm’s legacy after attending tech school for agronomy.

“Ever since I was probably four or five, I can remember going with my dad and following him around and just absorbing [the] knowledge that he had,” Furseth says.

Farms have been rooted within our society for so long, and with multiple generations of farming, traditions and techniques form through the years. With the invention of new technologies, farms worldwide are also pushed to change, especially with their long-time traditions.

“When I was little, you had to steer a tractor back and forth across the field, and now we have a GPS [on the tractor] so it can steer itself from one end of the field to the other [and] in recent years we use cover crops on our farms [as well],” Furseth says.

Along with having a GPS feature on tractors, Furseth mentions how their farm opted not to perform tillage on their soil. They made this change in the mid-2000s. Tillage essentially manipulates soil through mechanical tools to prepare it for new crops.

“I know before I was born, in the 80s and 90s, they did a lot more tillage […], [but] not [tilling] the soil is kind of healthier in a way, so that’s what we’re striving for,” Furseth says.

Although technology shifted many families within the farming world, one “tradition” that remained in the Furseth farms is family.

“One thing that’s different about our farm is our family always has kind of stuck together; my grandpa has three other brothers, and when they first [started farming], they were probably my age. […], [Many] would have probably split up […] and farmed on their own, but they stuck together. [That] kind of changed how our farm operates because we’ve all stuck together,” Furseth further explains.

Another farm in Stoughton with its own set of traditions is Lovefood Farm. David Bachhuber is the one who established Lovefood farm. He began his career as a neuroscientist at UW-Madison for 12 years. Still, around his ninth year, Bachhuber felt like he had completed his work. At the time, he had a passion for gardening, which then turned into a passion for farming.

Lovefood is a community-supported agriculture (CSA) farm that predominantly grows mixed vegetables and herbs such as peppers, tomatoes, radishes, green onions, rosemary, and thyme.

“The way that [CSA] works is that at the beginning of the season, people will buy a share in the farm […] and [throughout] the growing season, they get a box of vegetables every week. […] It usually ranges from like eight to thirteen varieties of vegetables, […]. so we’re basically getting a loan from them at the beginning of the season, and paying it back with vegetables throughout the season,” Bachhuber says.

Lovefood farm sells to around 200 families via their CSA program, and they also sell their products at the Dane County Farmers’ Market.

A significant factor that affected farming traditions is climate change; Bachhuber found that greenhouses have benefited both him and his farm.

“One of the things that we’re seeing is that there is a larger number of extreme weather events in our current climate. And so we can be resilient in the field a little bit, but [some crops are] very sensitive. […] One of the things we’ve decided to go hard on is greenhouses. I can grow herbs in the winter. We sell those to grocery stores and restaurants, and then […] we can use those same tunnels to grow tomatoes in the summertime. […] We sell those all over the place so that we can get a very high-value crop,” Bachhuber says.

As a first-generation farmer, Bachhuber did not have any unique traditions passed down from his parents, grandparents, etc. Instead, he learned many techniques from his farming community.

Bachhuber makes holes in a plastic-type fabric and then plants crops into them. This method keeps the weeds and pest pressure down.

“I think that’s one of the values of being in this type of farming is there is much more of a push on flexibility and adaptability,” Bachhuber says.

Final Note

Stoughton is home to a beautiful agricultural community. From teaching to selling to farming, each and every part of our agricultural community has become a solid pillar of our society. From the food you see at the grocery store or your local farmers’ market to the food you eat at your favorite restaurant, it all comes from a farm. Farmers work day and night to ensure that the food we get on our table is of exceptional quality, but they do not do it alone. The respect and unity they have with their co-workers and family have shaped the firmness of our farming community. So make sure to thank our current farmers for providing everything, from the cheese and wheat in our favorite cheeseburger to the clothes you find in your closet.

Jade is a senior and this is her first year on staff.

They are also on Madrigals head table and are involved with SHS’s fall musical. In her free...

Junior Bhoomi Patel is a staff writer for the Norse Star. She enjoys how Norse Star gives her the abilities to engage with the community.

Outside of...